Yesterday I saw two museums for the first time: Gustavianum and Evolutionsmuseet Paleontologi.

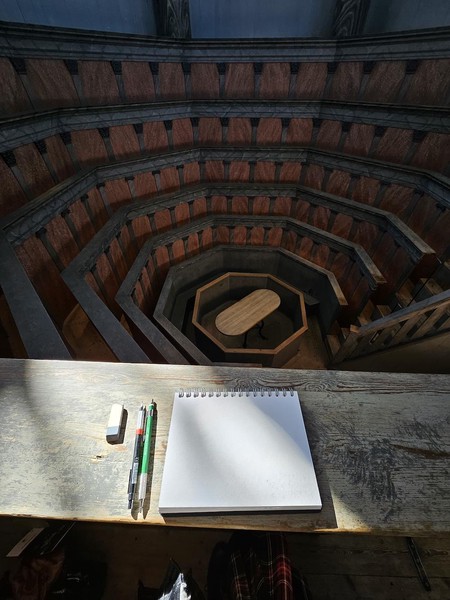

Urban sketching at Gusativanum

The Urban Sketchers meetup took place at Gustavianum Sunday morning. The museum is huge. We didn’t have time to go through it at the pace it deserved, because the idea was to find something we wanted to draw and get started. But I loved the glimpses I got of all the collections and will definitely be returning to appreciate them properly.

I already had my sights on, of course, the anatomical theatre. The day before, I went to an opening at Konstmuseet of an exhibitiom that was largely inspired by the theatre, so it was already on my mind. But I figured that it’d probably be very busy, and that lots of other participants would want to draw it, too. I’d also been warned that it would be very cold. So I figured we’d go look at it and then I’d probably go down and focus on sketching something else.

When we got there in our quick run-through of the place, it was still empty except for us. I went up the steep steps to one of the higher observation spots. It was cold, but when the sun hit my face through the windows up above it immediately warmed me up. So when everyone else began heading out to see the rest of the museum and choose their subjects, I decided I’d found mine.

I stayed there for about an hour. It was so peaceful, and empty almost the entire time. Sometimes, it would be completely silent and then the sun warming up my hands and face almost sounded like it was whispering on my skin. Then, a brief gust of wind would remind me what sound really is as the structure creaked around me.

As I said before, I haven’t drawn in years, so my attempts were… well, they were attempts. Toward the end I also tried to sketch one of the pillars at the top.

Next time we’re sketching at the Museum of Medical History.

Behind the scenes tour at Evolutionsmuseet Paleontologi

After Gustavianum I walked over to Evolutionsmuseet, where a friend and I met for a behind-the-scenes tour of the paleontology department. The tour was guided by Benjamin Kear, who is the curator of vertebrate palaeontology at Uppsala University.

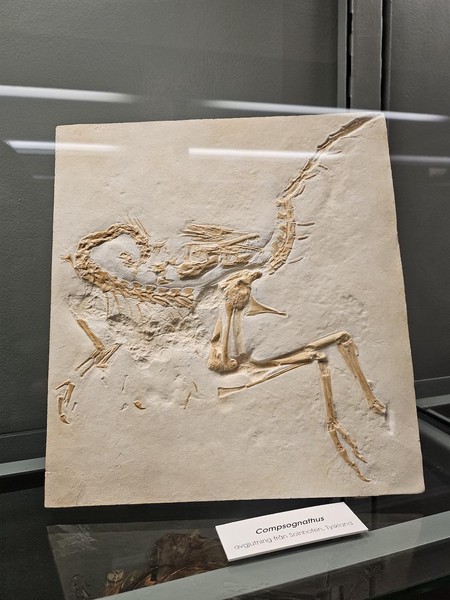

As a childhood dinosaur enthusiast, there was so much cool stuff in this tour! We walked through the various collection rooms and even got to hold some of the specimens to check them out up close. Feeling the serrations of a t-rex tooth under my thumb was kind of unreal as it hit me how old this thing in my hand was, and what kind of life it belonged to. We also got to hold part of a t-rex jawbone.

Here are some highlights from the notes I took during the tour:

- Evolutionsmuseet Paleontologi building was built in 1931, with the collection (public property belonging to the state) going back to 1658.

- They have a fish from Estonia that is 430 million years old!!!

- We got to hold a 319 million old poop. In our hands.

- A Plesiosaur was discovered to have melanophores, which are pigment cells that enable color change. Like lizards today, the Plesiosaur was likely able to change colors.

- Melanin is very resilient in the fossil record, so we got to see a fossil of a fish with its actual eye color still intact.

- 252 million years ago, a land-living animal took its first step back into the ocean. This evolutionary jump - land-dwelling back to water-dwelling - is perhaps even more impressive than the evolution of flighted birds.

- A t-rex likely had spots or block colors to break up the pattern of a large animal and assist with camouflage. It likely had quills or ‘proto-feathers’ around its head, and maybe around the ulna (on its arms).

- We saw the jaw bones of a whale, with one of them being full of abscesses, having rotten away as the animal died of septicemia.

- Whale bones are notoriously finicky to handle as they are so brittle. They’re very ‘spongy’, because whales contain a lot of oil for buoyancy. This oil permeates their bones, which is why the bones are spongy and fragile.

- The Evolution Museum’s collection is about to absorb the Swedish Geological Survey collection, which will bring it up to 2 million specimens (need to fact check this to make sure I wrote the number down right!)

- I had thought that by the time we discover these fossils, none of the original material the bone was made from is left, but it turns out that is not the case! For example, that t-rex tooth was encased in mineral matter, but on the inside it’s highly likely traces of the original tooth material remain.

- The paleontology building will soon be refurbished, which means the entire collection will need to be moved for the duration.

- Uppsala has the highest density of paleontologists in the country.

“The fossil collections never grow old…”

One of the coolest parts of the tour for me was learning a little bit about how our methods of inspecting the same fossils evolve over time. The same fossil found years and years ago will likely reveal new secrets today.

For example, we now have the ability to look into the internal structure of fossils using particle colliders. Apparently CERN does some of this work! Synchrotron optics is extremely exciting to paleontologists these days, and out of all the experiments I’ve heard places like CERN perform, this area just never crossed my mind before. Photon colliders allow us to look inside a rock that may contain valuable bones without risking destroying them. We got to hold a 3D print of a skull found in just such a way, as well as see the original fossil it was ‘scanned’ from using synchrotron radiation.

The tour also placed a lot of focus on the context around each fossil being the most important thing, as opposed to the object itself. As we discover more from the area a fossil came from, new context and knowledge can be built around the ecosystem as a whole. Fossils are now tagged with lots of critical metadata which is searchable virtually by researchers to gain valuable context about various finds.

After the tour, we went up to the main open floor collection space, where we got to see some full reassembled dinosaur skeletons.